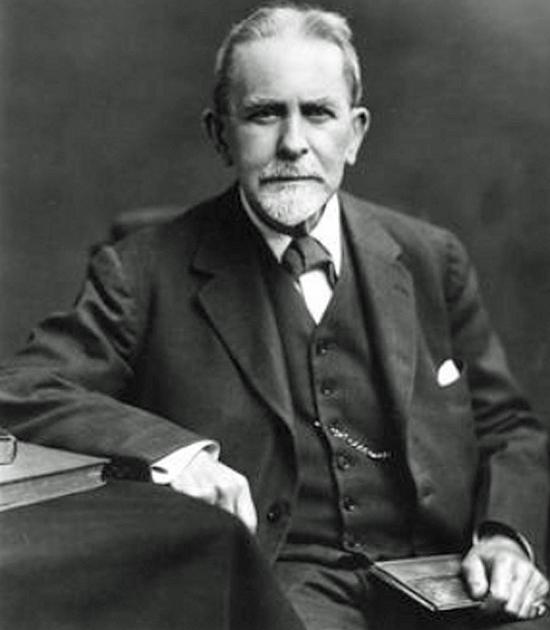

PROBABLY the most honoured academic ever educated in Helensburgh treasured his memories of his boyhood in the burgh until his death aged 87.

Sir James George Frazer, a leading social anthropologist, folklorist and classical scholar of his time, was a key figure in the early stages of the modern studies of mythology and comparative religion, and greatly influenced writers and thinkers such as D.H.Lawrence, T.S.Eliot and Ezra Pound.

Born in Brandon Place, Glasgow, on January 1, 1854, he attended what was then called Larchfield Academy — later Larchfield School, now part of Lomond School — while living with his parents at Glenlea, 16 East Argyle Street.

His fondness for his childhood haunts shone through in a piece he wrote at the age of 76 entitled ‘Memories of Youth’, included in a collection of essays published by Macmillan in 1920, entitled ‘Sir Roger de Coverley and Other Pieces’.

Recalling Glenlea and the little East Burn which runs beside it, he wrote: “Tonight, with the muffled roar of London in my ears, I look down the long vista of the past and see again the little white town by the sea, the hills above it tinged with the warm sunset light.

“I hear again the soft music of the evening bells, the church bells of which they told us in our childhood, that though we did not heed them now, we would remember them when we were old.

“Across the bay, in the deepening shadow, lies sweet Rosneath, empowered in its woods, and beyond the dark and slumbrous waters of the loch peep glimmering through the twilight the low green hills of Gareloch, while above them tower far into the glory of the sunset sky the rugged mountains of Loch Long.

“Home of my youth! There in the little house in the garden — the garden where it seems to me now that it was always summer and the flowers were always bright — the garden where the burn winds wimpling over pebbles under the red sandstone cliffs — I dream the long, long dreams of youth.

“A mist, born not of the sea, rises up and hides the scene. And as the vision fades — like many a dream of youth before — I look into the night and hear again the muffled roar of London.”

The eldest of four children of wealthy Daniel Frazer, senior partner of the Glasgow pharmacist firm of Frazer & Green, and his wife Katherine, nee Bogle, James excelled in Latin and Greek at Larchfield Academy.

He entered Glasgow University in 1869 and studied Latin under George Gilbert Ramsey, Rhetoric under John Veitch, and physics under the great Lord Kelvin (Sir William Thomson), originator of the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

In 1874 James began studying at Trinity College, Cambridge. He graduated with first-class honours in Classics in 1878, and because of a dissertation on Plato, he was elected to a Title Alpha Fellowship in 1879.

Over the coming years his fellowship would be renewed three times, in 1885, 1890 and 1895.

Next he moved to London and entered the Middle Temple to study law. This he did mainly to appease his father, who felt that he was wasting his talents on academic subjects and needed a trade.

Four years later, in 1882, James was called to the bar, but he never took up practice. Instead he chose to continue his preference for philosophy and anthropology.

He returned to Cambridge and embarked on a programme of research and writing, starting first with a translation and commentary on Paesanias, a Greek travel writer of the second century — a work he finally finished with six volumes in 1898.

One method he used in his research was to send out questionnaires to missionaries, doctors and administrators throughout the empire.

He requested information on the customs, habits and beliefs of local inhabitants, a mammoth undertaking. His comparative study of the incoming information led to his first book, ‘Totemism’, published by Adam and Charles Black in Edinburgh in 1887.

Macmillan published what became his most celebrated work, ‘The Golden Bough’, in 1890. This first edition was in two volumes and became an instant classical best seller, and he published two further larger editions.

The second edition, in 1900, was in three volumes and the third, in 1915, had 12 volumes.

From 1890 James spent the next six years travelling extensively in Europe, before returning to Cambridge where in 1896 he met and married Lilly Grove, a French widow with two teenage children, daughter Lilly Mary and son Charles.

Born Elisabeth Johanna de Boys Adelsdorfer in Alsace, her first husband was British master mariner Charles Baylee Grove, who died suddenly.

A devoted wife and an authority and writer on the ethnology of dance, Lilly did much to promote his work in France, Germany and Italy.

In 1904 James studied Hebrew, and in 1910 he accepted the post of Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Liverpool. But he never liked the noise and bustle of the large industrial city and longed for the peace and quiet of Cambridge.

He returned to Cambridge a year later and continued his research, writing, and translating old manuscripts from Hebrew, Latin and Greek.

In 1914, at the start of World World One, he was knighted. Sir James and Lady Frazer spent the war years in a small flat in the Middle Temple in London, to which his nominal membership of the bar entitled him.

Lady Frazer devoted herself to guarding his peace, and encouraging him to write and continue his researches.

During the post war years they travelled much of the continent together pursuing his research. Then, in 1930, while giving a speech at the annual dinner of the Royal Literary Fund, Sir James was suddenly struck down with blindness as his eyes filled with blood.

Despite this handicap, he simply engaged secretaries to write his dictation and continued with his work.

While his books contain a mass of ethnographical information, academics and scholars of today — while respecting his early work — dismiss his findings and theories as belonging in the past.

Nevertheless his work is considered instrumental in the development of the academic study of religion during the late 19th and early 20th century.

He paved the way to study religion as a cultural rather than theological phenomenon, and saw a progression from magical through religious to scientific thoughts and beliefs.

Between 1887 and 1913 he published 15 important works on anthropological subjects, the most recent of which were “The Beliefs in Immortality and the Worship of the Dead”, “The Scapegoat”, and “Balder the Beautiful”.

But Sir James is best remembered for ‘The Golden Bough’, which greatly inspired early pioneers of the Wicca and Witchcraft movement.

For his exceptional services he was created a Knight in 1914 and awarded the high honour of the Order of Merit in 1925.

He was made LL.D. (Oxon), Ltt.D., F.R.S., F.B.A., F.R.S.Edin., Litt.D. of Durham and Manchester, and from France received the honour of Commander of the Legion d’Honneur. He also received honorary doctorates from the universities of Paris and Strasbourg.

But despite such wide recognition, he never forgot his old school, and in 1904 he became of a member of the Old Larchfieldian Club. He also presented the prizes one year.

When he received the Freedom of the City of Glasgow in April 1932, not to put too much strain on him, the ceremony took place in the City Chambers, in the presence of members of the Corporation and invited guests instead of before the usual large gathering in the St Andrew’s Halls.

Sir James recalled his schooldays in glowing terms, and added: “When I think of the famous men on whom a similar honour has been bestowed in the past, I am proud to be deemed worthy of being added to that illustrious company. I am humbled by reflecting how far the talents and achievements of these eminent men excel my own.”

He also spoke of his boyhood, when he would spend hours after school roaming around Helensburgh and Garelochside.

There, surrounded by hills and forests, the breeze rippling his shirt and blowing through his hair, he would listen to the faint bells of the burgh churches. Until his middle years he even spent most of his holidays at home.

In his speech he also revealed that his life might have had a very different outcome.

“My father,” Sir James said, “had a little house in Helensburgh where my two sisters, my brother and myself spent the happiest years of our childhood.

“Through the garden flowed a burn, which had its source in a reservoir high up on the moor. One day while we children were playing on the banks of the burn we noticed that it was unusually swollen and that the current ran fast and strong.

“So we called it the ‘Falls of Niagara’, and continued to play beside it as such.

“But the game was suddenly interrupted by the arrival of a friend of my father, who came in great haste to tell our mother that the reservoir had burst its banks, that the water was rushing down the hill in a great torrent, sweeping everything before it, that our house was in danger, and that we must clear out of it without a moment’s delay.

“We children were hurried away from the ‘Falls of Niagara’ to a place of safety in the west of the town.

“The warning did not reach us too soon; for a few minutes later the flood came roaring down and swept clean away a massive stone bridge which spanned the stream just above our house, littering with its ruins the garden in which we children had been playing so shortly before.

“Had we not thus escaped from the ‘Falls of Niagara’, I might not be here today to tell the tale and to receive the freedom of the city.”

Sir James died on May 7, 1941, and Lady Frazer a few hours later. They were buried in one grave at St Giles Cemetery, Cambridge, on May 14.

The service in the Chapel of Trinity College was attended by many senior representatives of Cambridge, Glasgow and London Universities.

email: milligeye@btinternet.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here