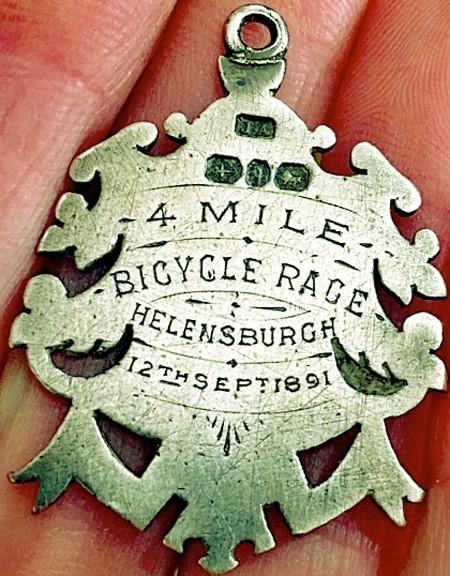

A SEARCH for information about 1890s cycling in the Helensburgh area has already proved fruitful.

I asked for help in last week’s Eye on Millig following the discovery of a medal for a 4-mile bicycle race in Helensburgh on September 12 1891 by Lesli Hiller, of Long Island, New York, in her grandparents belongings.

Local historian Alistair McIntyre, a director of Helensburgh Heritage Trust, was up to the challenge and has produced the results of his research into the pastime.

He tells me: “Helensburgh has hosted an impressive number of cycling agents and cycling clubs over the years.

“To an extent, this is a reflection of both the many turns and twists that have taken place in the story of the bicycle itself, and changes in society as a whole.” The birth of the bicycle took place amid the turmoil of Revolutionary France near the end of the 18th century, when a young Parisian demonstrated a propulsion device consisting of two wheels, fixed one behind the other, joined by a frame, and surmounted by a ledge to sit on.

Forward motion was produced by pushing on the ground with alternate feet.

With the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815 and the ensuing peace, word of the invention soon crossed the Channel.

The imposing names of ‘swiftwalker’ and ‘pedestrian curricle’ were coined, though it was the nickname ‘hobby-horse’ that won the day.

Initially the toy of Regency bucks, the hobby-horse never really took off for several reasons.

Clad with wooden spokes and iron tyres, and initially with no means of steering, it was heavy and unwieldy, and groin strains and other injuries could easily be suffered.

Perhaps worst of all, it was the butt of endless jokes and cartoon sketches, and it is doubtful if many hobby-horses ever reached Helensburgh.

As with so many inventions, it was a Scotsman, Kirkpatrick MacMillan, a Dumfries blacksmith, who made the big breakthrough.

In 1839, he developed the first true bicycle, in the sense of a two-wheeled velocipede that could be propelled without the need to touch the ground.

The feet of the rider pushed on treadles, linked to the rear wheel by iron connecting rods. But his invention failed to spark much interest, and MacMillan never sought a commercial outcome.

It was left to others to drive development forwards — once again the wags had their way, and various improved bicycles were cruelly, if truthfully, lumped together under the term ‘boneshakers’.

A significant breakthrough took place in 1870-71 with the introduction of the ‘high wheeler’, soon to become known as the ‘ordinary’.

This is the bicycle known today as the ‘penny-farthing’, though this term was only coined around 1890, when the machine was in its twilight years.

James Farley from Coventry emerged as an inventive genius from about 1870 onwards to the extent that he is known as the father of British cycling.

Over the next decade, he brought in repeated improvements to the high wheeler. Wire spokes set tangentially on the wheels were developed, as were solid rubber tyres, and hollow parts for the frame. Ball-bearings and pedals were already available.

Such features brought down the weight considerably, and produced a much better performance.

Farley had working under him a William Hillman and a George Singer, later to become famous in their own right as motor car manufacturers — underlining perhaps the position of the car as junior partner to the bicycle!

The penny-farthing consisted of a very large front wheel, above which sat the rider, supplemented by a relatively small wheel at the back for balance.

The large wheel, which was the driving wheel, proved capable of generating much higher speeds than previous bicycles, with a really proficient rider able to reach 20 mph on level roads.

The bigger the wheel, the more speed, the only limiting factor being the length of the rider's legs.

Other attractions included a clear view of the road and surroundings, being well removed from mud splattering, and, thanks to the large leading wheel, the ability to cope with a fair degree of roughness in the road surface.

There were a number of disadvantages. Mounting, dismounting, and the elevated seating position — the big wheel could be from 4-5 feet in diameter — could be really intimidating.

Should the rider be brought to a sudden halt by hazards such as children, animals, or loose stones, he could be thrown forwards, and even end up doing an involuntary somersault.

If the rider's foot became entangled with the spokes, the outcome was similar.

The actions of the malicious, resentful or jealous included the placing of a line of bricks across the road, or the thrusting of a stick between the spokes. A crash could easily be the result.

Another practice was to throw a cap at the rider or machine. Seemingly innocuous, this could at best irritate the rider, but at worst, it could cause a crash, especially if the cap jammed between the spokes.

On the other hand, there could be occasions when the rider himself was at fault. Showing off doubtless happened at times. One offence that came more and more before the courts was the charge of “riding furiously”.

Despite all the challenges posed by riding the high-wheeler, this was the design that came to dominate the market — and it was almost certainly the first bicycle really to make its mark in Helensburgh.

This meant that use of the bicycle was restricted to the younger, more athletic, and generally the better-off male members of society.

The earliest reference to the presence of bicycle riders in Helensburgh that has so far come to light is in an 1877 issue of the Dumbarton Herald newspaper, which reported that three members of the West of Scotland Amateur Bicycle Club visited Helensburgh.

They set off from Glasgow at 2.15pm, and arrived in the town at 5.15pm. Beginning the return journey at 6.45pm, they reached their starting point at 10pm, having clocked up 44 miles.

A much better picture can be gained from a July 1880 issue of the same newspaper.

“Bicycling has become a popular amusement in Dunbartonshire, as elsewhere,” it stated. “Unlike the machines of old, which could weigh up to a hundredweight, the modern version comes in at no more than 48 lbs.

“Wheel sizes can range between 44 to 62 inches in diameter. The ordinary rider favours a wheel diameter of 50 to 52 inches, while 55 to 60 inches are preferred by the professional. A first-rate bike costs £25, while a standard model costs £10.”

By this time the county had three cycling clubs. The Dumbarton club was formed 1879, and had 20 members. The club met twice a week, if the weather was suitable, and they cycled to some place of interest. The Vale of Leven club was started in 1880.

The Helensburgh club was started in September 1879 with five members which had risen to 18.

The president was J.W.Burns of Kilmahew, the captain George Logan, secretary David J.Nicol, and treasurer James Logan. Members rode to Cove, Dumbarton, Ardlui, Mambeg, Arrochar, Luss, and Balloch.

There was no mention of the club in the Helensburgh directory of 1883, so it had probably folded — yet there is a listing of Helensburgh Tricycle Club, which sounds much less glamorous.

It not until 1880 that a really viable tricycle became available on the market. The idea of having three wheels rather than two was certainly attractive —mounting, dismounting and keeping balance was easy.

The typical tricyclist would have been older than most cyclists, and did not need to be athletic. It received a big boost when an early purchaser was Queen Victoria.

In 1881, Her Majesty was in residence on the Isle of Wight when her attention was drawn to a tricycle which had overtaken the Queen’s coach — and it was being ridden by a young lady.

Whether or not Her Majesty was amused is not recorded, but she was certainly impressed, and immediately had two tricycles ordered.

The tricycle was something that could be used by women, and adverts were quick to portray young ladies on tricycles. Women generally did not use bicycles, particularly the high wheeler, as their long and voluminous skirts and petticoats spelled disaster.

The 1881 Helensburgh Directory lists the Tricycle Club captain as Provost John Stuart, the secretary and treasurer David Mitchell, and the committee members John Mitchell, Maxwell Hedderwick and William Lunan.

A contemporary writer said of Provost Stuart: “He may be seen of an evening in the company of a troop of friends, spinning along the Garelochside, each seated on that modern vehicle, a tricycle.”

The same directory carries an advert on behalf of the firm of Macneur and Bryden, listing various tricycles for sale, but no bicycles. Better known as a stationer and publisher, the firm ran ran a cycle warehouse as well until around 1926.

Another surprise as a pioneering cycling agent was R. & A.Urie, usually thought of as a dealer in china, glassware and stoneware.

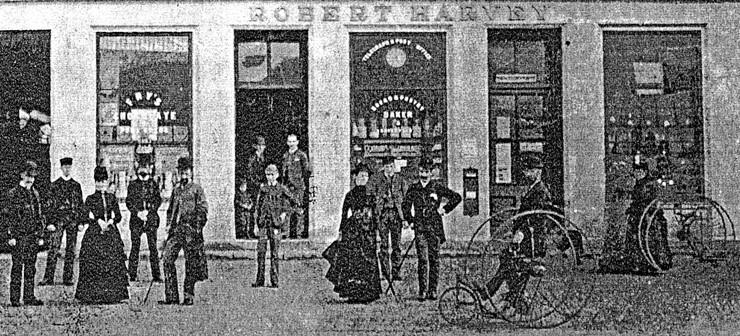

Yet another to rasp the new marketing potential quickly was Robert Harvey, the postmaster and grocer at Cove, who by 1881 was advertising ‘Premier’ bicycles and tricycles in the local press.

When Helensburgh Post Office stepped up its Garelochside deliveries of mail to four times daily in 1888, it used tricycles to take the mail as far as Shandon, beyond which post-runners were used.

The Helensburgh Directory of 1889 makes no reference to cycling clubs, which suggests the Helensburgh and Gareloch Cycling Club of 1887 was no longer functioning, but a new Helensburgh Cycle Club was formed in 1892 and a Ladies Cycle Club around 1898.

The heyday of local cycling had arrived.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article