This week's Eye on Millig column looks at the story behind a long-held belief that dead Colquhoun clansmen are buried in Glen Fruin above Helensburgh...

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

IT BEGAN as a mystery and ended as a mystery...but there were some fascinating discoveries in between.

The starting point was the desire by a group of local people to have a memorial for those who lost their lives in the Battle of Glen Fruin on February 6, 1603, and they wanted to confirm a long-held local belief that a burial mound in the glen was where dead Colquhoun clansmen were buried.

Excavation of the mound near Strone Farm took place in July 1967. It confirmed what the mound was, and that it was not the resting place of the Colquhouns.

That July it fascinated Advertiser readers, and this is how it unfolded.

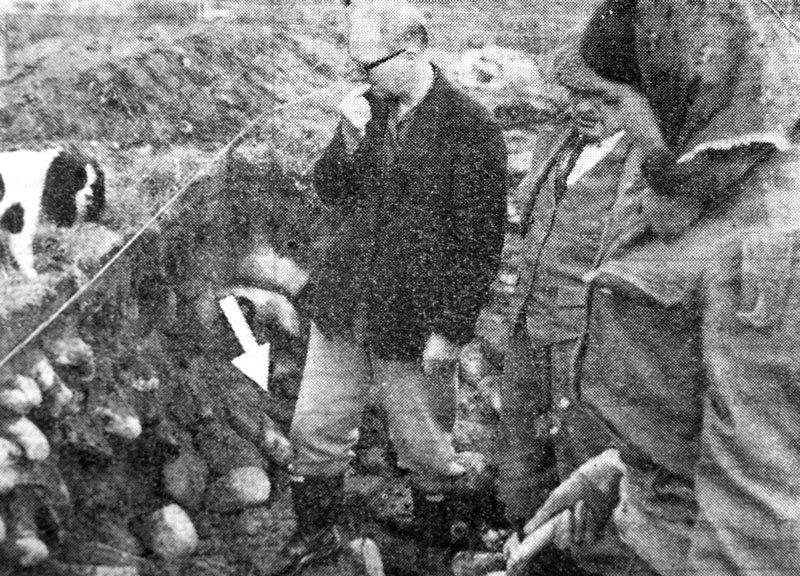

Jack G.Scott, curator of archaeology, ethnography and history at Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, used his trowel to explode a historic myth and uncovered proof that local historians had been misled for years.

For years local people had pointed out the mound near to the Hydro Ballistic Research Establishment as the exact spot where the dead clansmen were laid to rest after being slain by the MacGregors.

Legend had it that the grass never grew there in earth steeped in Colquhoun blood.

“But it seems that they got the wrong mound,” said the then Laird, Sir Ivar Colquhoun of Luss, a direct descendant of the clansmen who were killed.

“I gave permission for the mound to be excavated to discover whether it was in fact the burial ground.

“They thought that the Colquhouns and one or two of the MacGregors were buried there too.”

When the mound was first probed no evidence of Colquhoun dead could be found, and instead the diggers came upon clues to a Bronze Age encampment under the mound.

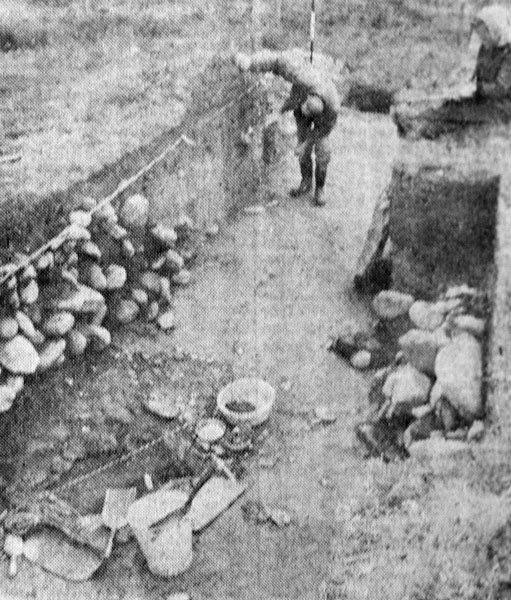

To make absolutely sure that there was no historical blunder, Mr Scott was called in to investigate. After digging in the glen for a few days, he reported: “We think it is probably a prehistoric mound, and possibly a Bronze Age cairn.

“I am fairly convinced it is not the Colquhoun burial ground. But I soon realised it was not just a natural hump. And if it is not, what was it built for?”

His excavations were slightly complicated by a previous attempt. He said: “Whoever it was seems to have taken his bulldozer right round the side.”

He pointed to a ring of stones round the mound, and said he had a strong feeling they had not been disturbed, although one stone was loose.

“It was the practice in the Bronze Age to put a ring of stones round the cairn,” he said.

He found in the centre of the mound more boulders or ‘cobbles’ and at ground level a layer of almost purple soil.

“It contains carbon,” he said. “Before the cairn was built it was the practice to clear the ground by burning it, and that could explain the carbon.”

He thought the digging might reveal below ground a pit with stone slabs making walls to form a box almost 6ft by 2ft 6ins, called a ‘cist’. The body would be buried in it in a crouching position.

“What we hope is that a pot or a flint may have been buried with the body as a burial gift,” he said.

His team quickly made two important finds, which they marked with long pins with bold red tape attached.

“Where the first pin is we found what seems to be a piece of cremated bone. I would think it is probably human, but I am not an anatomist,” he said.

The second pin showed where a flint, of uncertain age, was found.

He explained that later in the Bronze Age burial of the body was superceded by cremation on a funeral pyre. Often burial mounds were

used for the cremation, so that the Glen Fruin mound could contain the last remains of two bodies.

The cremated body would then be covered and trees planted.

“Trees were planted here on top of the mound,” Mr Scott said. “But they were removed in the previous digging and thus may have disturbed the later Bronze Age burial.”

He originally intended to be in the glen for a week, but he stayed for ten days.

Did the first venturing bands of the Beaker People steal through the mists of the Fruin and settle there 4,000 year ago? Or was the desolate glen a sacred spot where, with rite and ceremony, their dead were laid to rest?

These questions can never be completely answered, but Mr Scott’s excavations of the mound proved that the glen was known and probably lived in during the middle Bronze Age.

“It was not known before that people knew of the glen and lived in the area, but of course we suspected it,” said Mr Scott.

“The cairn is especially valuable in Dunbartonshire and Argyll, where there is only a limited amount of evidence of the Bronze Age. There is only a limited amount of suitable agricultural land to live from around that area.”

Back at his museum desk, Mr Scott gave his conclusions. “We are convinced it is a Bronze Age burial site,” he said.

“First of all there was a stone-lined pit or cist, covered by a slab, in which we found a large quantity of cremated bones which almost completely filled the pit. I think they were the bones of more than one person, possibly two or three.”

When they lifted the slab, the digging team were the first people to look into the pit for over 3,000 years.

Frequently Bronze Age cists contained a burial gift, such as a pot or a flint. But on this occasion only bones were found in the cist.

“It is a pity,” Mr Scott said. “Had there been something we could have confirmed the date of the burial.”

The cist was below ground level, with the capping slab at ground level. Above it was first a layer of clay, then a two feet layer of smallish, rounded boulders or cobbles.

Over that was another layer of clay, about three feet. Round the cairn was a whole kerb of quite large boulders.

“The whole thing was finished off with stones, so that from a distance it looked like a stone cairn,” Mr Scott said.

“It is typical of the cairns built in the early and middle Bronze Age. I think it more likely to be the middle Bronze Age as by that time

cremation had replaced inhumation. I would estimate the date as somewhere between 1500 and 1300 BC.”

Mr Scott and his team proved that there had been a slight ditch round the cairn, which was filled up before the cairn was built.

He said: “Whatever it was certainly preceded the cairn. The ditch may have been marking a sacred area or something, but that is only a guess.”

Asked what the importance of the dig was, he replied: “It does show that this part of Scotland partook in the general civilisation of the middle Bronze Age.”

Before they left the site, his team filled in the trenches they had dug, replaced the cap stone slab and covered it, in the hope of preserving the site as much as possible.

Was there ever a Colquhoun burial mound it? If so, where is it?

W.C. Maughan, in his book ‘Annals of Garelochside’ published in 1896, told of 140 Colquhouns buried in the one place after the battle.

He wrote: “From the summit of the road which winds up the side of the hill above Faslane Bay, the traveller can look down upon the upper part of the glen, with the trees round Strone Farm, near where the battle was fought.

“A little way from the roadside, near the house, is a large grey stone, beside which John Macgregor, the chief’s brother, who was one of the few slain on that side, was buried.

“The river Fruin has gathered strength and volume since leaving the high glen from when it rises, and curves round the head of the glen, beside the wood — a pure stream of limpid sparkling water.

“Bounded by the river on one side and the road along the glen on the other, there is a large level field of fifty acres in extent, now given over to natural pasture, though thirty years ago it was waving with the golden grain of autumn.

“A square mound, measuring about sixty feet on each side, crowned with fine, rugged, red, old Scotch firs, marks the spot where were buried the bodies of the gallant clansmen who fell on that bleak morning of early spring.

“An old wall used to environ the mound a number of years ago, but it has long since mouldered away.

“There were a good many more Scotch firs, also, that since succumbed to the wintry blasts rushing along the glen with devastating effect. It is a lonely and impressive ravine.”

That certainly sounds like the site of the excavated mound, which is about 200 yards south east of Auchengeoch farmhouse, except for it being a ravine — unless he considers the whole glen as a ravine.

Maughan wrote that past Auchengeoch comes Auchenvennel, then Balknock farm.

He continues: “Here, in the middle of the field, is an old burying place, though beyond one or two flat stone slabs, scarcely seen above the turf, there is little to indicate that this was once used as a spot for the purpose of sepulture.”

He claimed that the mound now proved to be of the Bronze Age “marked” the spot where the Colquhouns were buried.

As the mound had been in existence for thousands of years before the battle, could the bodies have been buried near the mound — a ready-made monument? Or were the dead clansmen laid to rest nearer Strone?

Local artist Gregor Ian Smith and the others who wanted a monument could not be sure, but the following year it was erected on the hill at the far end of the glen, overlooking the battlefield.

It was restored by Helensburgh Heritage Trust in 1997, with the help of the Friends of Loch Lomond, Clan Gregor and BP.

Last year the Heritage Trust arranged for cleaning the monument and repainting the lettering.

The Trust had become aware that access to the monument from the road was becoming increasingly difficult, partly because of the state of the path and partly because of the growth of surrounding shrubs such as whin and birch trees.

The work involved the removal of most of the nearby shrubs and trees, to make access easier and to improve the visibility of the monument from the road.

Steps were built up from the road to the monument, with a handrail alongside, and a bench was constructed near the monument. Further clearance work was undertaken recently by Luss Estates.

email: milligeye@btinternet.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here