AFTER the Advertiser revealed this week that the Helensburgh Community Woodland Group is preparing a public ballot on proposals to purchase two sites in the town for development, columnist Ruth Wishart has her say on territorial disputes...

********

THE curator was taking me round the private collection in one of the stately piles owned by the then Duke of Buccleuch.

Any of the old masters on the wall could have bought up a suburban avenue in Scotland, or a house in central London.

Just think, he mused aloud. You could walk across this part of Scotland without leaving Buccleugh land. Hardly surprising I suppose. When Andy Wightman, now a Green MSP, calculated private land ownership in 2010, Buccleuch estates topped the list with 241,887 acres.

More generally, Wightman worked out that fewer than 500 people owned half of all private lands. Whatever your politics, you can’t believe that to be healthy.

Indeed perhaps the current Duke considers the situation less than ideal. Earlier this year he announced plans to sell off 25,000 acres, and community groups whose ancestors were part of the lowland clearances have indicated their interest.

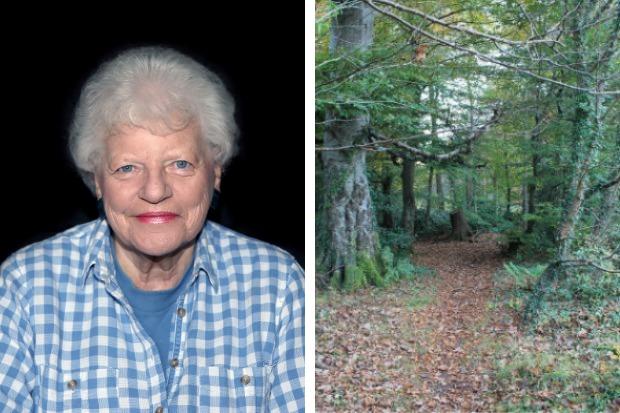

What has all this to do with our patch? Well, there is a community land buyout on the cards for patches of land at Castle Woods and Cumberland avenue. The owners, who bought the territory from the MoD, want, surprise, surprise to build more houses.

But the Helensburgh Community Woodland Group are set on a community buyout. They’ll need to get over 50 per cent in a ballot to use land reform legislation geared to helping such bids.

READ MORE: Public vote on Helensburgh group's land buyout plans

Land has always been an emotive issue. The vast Scottish estates in the main want to keep the status quo claiming that their holdings create employment and are well managed. Land reformers say that current arrangements leave tenants and communities impotent to improve their own lot.

And, in truth, community buyouts have had mixed results. Brilliant improvements in islands like Eigg, more disappointing results on parts of Bute.

But there are important principles involved here.

The history of how that land was acquired is pretty chequered. When people intone that such and such a holding has been in the same family hands for generations, they speak the truth. They just fail to acknowledge what portion of that acreage was initially acquired by nefarious means, as Wightman argues in his meticulously researched book The Poor Had No Lawyers.

Some major holdings were built up by annexing previously common land, some by feudalisation, some from church property, and “reforms” of the laws which benefitted those who could afford to use them, he demonstrates.

Of course that is now history. And in the intervening years some of the acreage held by landowners and trusts has indeed been well maintained and managed.

Though you might argue that preserving huge tracts to raise grouse in order that annual visitors might pop up and shoot them is not the most laudable use of our native heath.

But some, and Eigg was a classic example, were used as personal playthings by a succession of owners who allowed the community to die and the infrastructure – such as it was – to rot.

READ MORE: 'End game in sight' says woodlands group over Helensburgh ownership battle

Eigg is also an example of where a well run community buyout can create prosperity, dignity, jobs, and attract the young energetic families every location needs to thrive and survive.

We are a strange breed, we humans. One of the first things home owners often do is erect fencing round their property, no matter how modest.

Some of the most long lasting and pointless feuds erupt over hedging. Who owns it, who should maintain it, how high it should be allowed to grow.

But when that territorial instinct runs to many thousands of acres, covering the tenanted homes of many hundreds of citizens, then ownership too often leads to an imbalance of power and a misuse of responsibility.

Even in the 21st century we hear of farmers being thrown off their land because it is owned by someone who sees a more lucrative use for it. Farmers who, like those from whom they lease their fields, can boast of generations of tradition and good husbandry.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here