In our latest Eye on Millig column, Leslie Maxwell looks back at the visits of circuses to Helensburgh and the surrounding area in the years after the two World Wars.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

THE CIRCUS run by Lord John Sanger returned to Helensburgh twice after the First World War, in 1919 and 1924.

The war had a devastating impact on the world of the circus, as with all walks of life, and many of the best artistes and performers gave their lives in the conflict. It is also believed that some of the animals had to be put down.

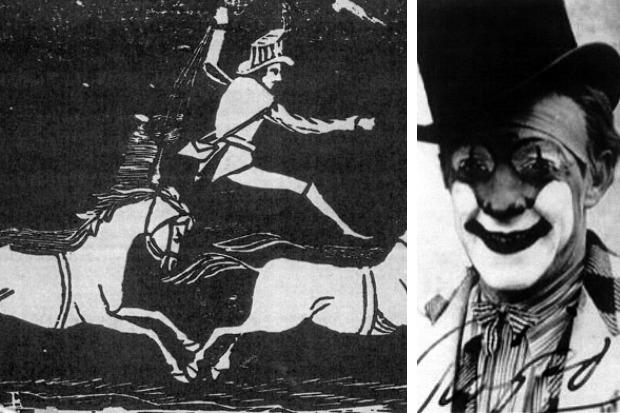

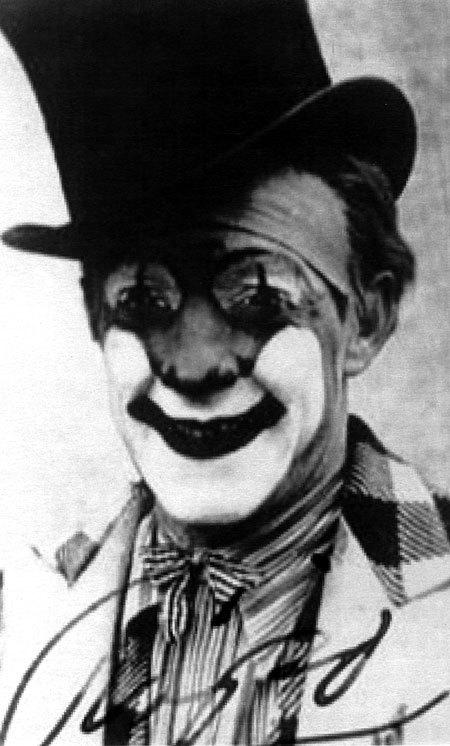

Afterwards, however, Sanger’s circus was able to regroup, and one of the star attractions was the clown ‘Pimpo’, real name James Freeman.

He is regarded as one of the greats of all time, and for many people, his appearance was the highlight of the show.

Rejected for military service in 1914, his agility and versatility were legendary, as he was as much at home with the artistes on the flying trapeze as on the sawdust.

A spectator recalled: “The one figure who remains distinctly in my memory is Pimpo the clown.

“I can see him now, sitting in a motor car, strapped to an elephant’s back, giving the hooter spasmodic blasts, while he raucously hailed the ringmaster, his diminutive figure clad in oversized dress-suit, a mass of ginger hair sprouting from the top of his head, and an enormous bow-tie.”

READ MORE: Pictures from the visit of family-friendly circus to the Hill House in Helensburgh

Pimpo was married to Victoria Sanger, the great-great-granddaughter of Lord George. Lord John was married to Rebecca Pinder, a member of another great circus family, while younger brother James was wed to Babs Pinder.

Local historian Alistair McIntyre, who has researched the visits of circuses to the district, says that the circus world is a very tight-knit one, and there were many marriages across the leading families.

Sanger’s 1919 visit was reported by the Helensburgh and Gareloch Times of July 16, which chronicled some of the behind-the-scenes efforts needed to keep the show on the road.

“Country districts are usually scattered, and to let them know Sanger is coming is no easy matter,” the paper reported.

“About five weeks ahead of the circus, an advance manager is sent out. He is followed about two weeks later by a number of bill-posters.

“This is very costly, and printing alone can cost £240 a month, which with extra bills and posters, along with payment for sites to display them, can cost another £260. With incidentals, the monthly bill can be £680.

“The salaries of artistes and performers come to about £7,000 per season, with wardrobe expenses some £1,800.

“The 320 animals cost a pretty penny in food alone. Each day, the bigger animals consume 100lbs of butcher meat, costing £5 daily, or £1,800 a year.

“The enormous quantity of hay needed is 800 tons, and in the course of the year, 3,650 quarters of oats are used, as are 150 tons of chaff. The enormous tent is another costly item.”

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: The life of the Helensburgh man who survived WW2 torpedo attack

Another matter was the essential business of obtaining permission from the relevant authorities well in advance, and payment of the associated charges.

The year after the 1919 visit to Helensburgh, Sanger’s circus was the scene of a terrible fire while at Taunton in Somerset.

The afternoon performance was in full swing, and people laughed as they watched Pimpo engage in a boxing match with a pseudo army sergeant, Leslie Sanger. Suddenly there was a scream of “fire!”.

Someone who was present claimed that the big top was completely consumed by fire in under five minutes. There were only two entrances, and five people lost their lives, while 20 were injured.

There were some heroics by circus staff as well as by others. The verdict at the coroner’s inquest was death by misadventure, with the fire probably being started by someone carelessly discarding either a lit match or a cigarette.

Despite this awful tragedy, Sanger’s circus and menagerie was back in Helensburgh in 1924. Lord John died in 1929, but Sanger’s circus carried on until 1941.

The Second World War was, if anything, more difficult for the circus world than the Great War, as there were labour and petrol shortages, along with rationing of food and other restrictions.

James Sanger later said: “I’m afraid it’s all over. The Blackout beat us.”

Helensburgh does not seem to have been visited by many of the great circuses during the 1930s, and there can be little doubt that factors like the Great Depression would have taken their toll. However, there were still opportunities for circus-goers.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: The Helensburgh medical marvel whose skill saved a circus chimp

For example, adverts appeared in the Helensburgh and Gareloch Times in 1935 and 1938 on behalf of Bertram Mills' circus, for performances in Greenock.

The London and North Eastern Railway Company ran additional steamers from Helensburgh, Craigendoran and the Gareloch to cope with the large numbers wishing to go to the circus.

As with a number of circus owners, Bertram Mills gravitated towards circus life on account of his great love of horses.

In the First World War he had been an army captain, charged with supplying fodder for horses.

When he set up his circus, he had no background in that field, but soon showed great flair and aptitude. Indeed, one circus writer stated that it was he who was the salvation of the post-war circus, offering a show that was as good as any on the Continent.

His was a very large concern, and two trains were chartered to move the show from one place to another.

Each show featured 21 acts on average, with the band playing around 120 snatches of music. The bandmaster took his cue from the movement of the horses, not the other way round.

It was particularly appropriate for the Bertram Mills circus to come to Greenock, as the Gourock Ropeworks had supplied not only his big top, but the smaller tents and ropes as well. Henry Bell’s pioneering steamship, the 'Comet', with its large squaresail, was also rigged by the same firm.

A big top might need a mind-boggling 4,500 square yards of heavy cloth, weighing in at around four tons, and the Gourock Ropeworks was one of the few firms capable of providing what was required.

After World War Two, there was something of a renaissance, and Helensburgh Town Council received quite a number of applications from circuses wishing to visit.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: Beechgrove Garden legend Jim McColl's Helensburgh roots

One was Tommy Pinder’s New International Circus, which had intended to come in 1959, but at the last moment, the town council withdrew permission on the grounds that East King Street Public Park required renovation.

But when Pinder’s tried again in 1960, they were successful, it being described as their first visit for many years.

Pinder’s circus claims to be the oldest British circus still in existence, as it dates back to Thomas Ord, the son of a minister, who was expected to study medicine.

Thomas, who was born in 1784, had other ideas, however, and took up an apprenticeship in horsemanship.

According to Thomas Ord’s grand-daughter, his master treated him very harshly, but in the event, the pupil exceeded all expectations and passed out as a star performer.

Thomas set up his little travelling circus in 1804, allegedly with a single donkey, but he soon built up an impressive show, touring all over the British Isles, and reaching as far north as the Orkneys, though it is not known if he visited Helensburgh.

At the age of 75, shortly before his death in 1859, Ord was still performing one of his trademark acts, standing upright on a horse galloping round the ring at full speed — a remarkable achievement, but perhaps worthy of a man known as the Father of the Circus in Scotland.

Ord based himself at Biggar, and was buried there, his headstone describing him simply as “Equestrian”.

Selina, one of Ord’s daughters, married Edwin Pinder in 1861. Pinder’s circus was founded by two of Edwin’s uncles in 1854, and when they decided to move their show to the Continent, the mantle of running Pinder’s British circus fell upon Edwin and his bride.

The young couple developed a show, the status of which may be judged by the fact that they were asked to perform before Queen Victoria on no fewer than three occasions. As a result it became known as Ord-Pinder’s Royal Circus.

Over time, though, another branch of the family set up its own circus, and it was Tommy Pinder’s New International Circus that visited East King Street Park in Helensburgh. There was a return visit the following year.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: The stirring story of a Helensburgh tea pioneer

Following the 1960 performance in Helensburgh, the next stop was Garelochhead, followed by Arrochar, and then Kinlochleven.

Local villages could expect to host few of the big names, but smaller shows visited from time to time. At Garelochhead, older residents recalled several sites being used, one near the bottom of Station Road, another at the site now occupied by the village's fire station.

Tommy Pinder’s circus was among the first to introduce motorised transport, though for a number of years they continued to use horses as well. By the 1960 visit to Helensburgh, however, horse-drawn transport would have been very much a thing of the past.

Circuses liked to refresh their shows from one year to the next, and one factor which expedited this was seasonal movement of performers from one circus to another.

The 'Scottish Samson' — real name William Beattie, from Blantyre — is a good example.

Having appeared with Fossett’s circus in the late 1940s, he performed with Rosaire’s circus in the early 1950s, Pinder’s circus in 1956, Joe Gandey’s in 1957, Mrs Pinder’s Royal No.1 circus in 1958, Tommy Pinder’s circus in 1959 and 1960, and so on.

The circumstances surrounding the end of Tommy Pinder’s circus was revealed by two of his sisters, Kathleen and Rosetta, when they were interviewed by a national newspaper in 1992.

Their circus was very much a family affair. They themselves, along with sister Lily May, had been bareback horse riders, while Edward, their brother, was the ringmaster.

Two other brothers, William and George, were the clowns, while brother Tommy, after whom the circus was named, as a lion tamer.

A major setback occurred in 1974 when Tommy suffered a slipped disc. It was realised that they were all getting older, and it was decided to call it a day.

Despite the rigours and dangers of such a demanding life, a surprising number of circus people lived to a very ripe old age — Rosetta died in 1998 aged 95, while Kathleen, who died in 2010, was in her 100th year.

* Final part next week.

READ MORE: Click here to catch up with all the latest news from around Helensburgh and Lomond

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here