This week's Eye on Millig column looks back at the story of the flying boats based at RAF Helensburgh during the Second World War following the death of Professor John Allen, one of the last survivors from those who served at the base.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

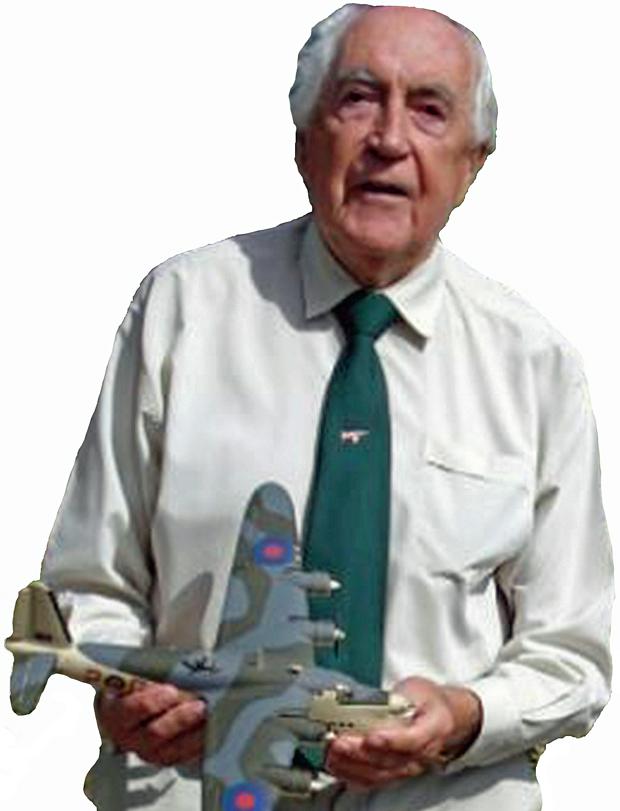

AN internationally respected scientist who was one of the last surviving people who served at wartime RAF Helensburgh, Professor John Allen, has died at the age of 99.

News of his death at Halesworth, Suffolk, comes from Mrs Frances McLaren, nee Shedden, who served alongside John at the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment (MAEE) at Rhu and Helensburgh during World War Two.

The secret flying boat base used RAF Helensburgh as a cover for its secret operations. John was a senior member of the scientific staff and contributed to a number of major advances in flying boat and seaplane design.

A few years ago, Professor Allen recalled his days at RAF Helensburgh for an Eye on Millig and Helensburgh Heritage Trust website article.

The Trust has access to the largest number of first-hand accounts on record of what life was like at RAF Helensburgh. However, the professor’s death breaks one of the last living links with this past.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: The three men who died in Clyde flying boat tragedy in 1940

John Elliston Allen, who was born in 1921, spent the war at MAEE, and returned with it to RAF Felixstowe in Suffolk at the end of 1945.

MAEE ceased operations in 1953, by which time Professor Allen had moved to Farnborough to supervise the ballistics and delivery method of Britain’s first atomic bomb.

He recalled how, at the outbreak of war, MAEE was evacuated from the English seaside town to the Gareloch, where the sheltered bay beside Kidston Point allowed work to continue without interference from German aircraft.

He returned to Rhu in recent times, staying at a bed and breakfast cottage, a short walk from the former MAEE headquarters, which is now the Rosslea Hall Hotel.

Professor Allen said that many new British and American flying boats and seaplanes, intended for Coastal Command use, found their way to Rhu, where he and his team of civilians assessed them.

Test pilots flew aircraft to their limits and perfected ways of launching airborne bombs.

Scientists like John Allen investigated stability; water impact during take-off and landing; performance; fuel consumption and any problems that arose with trials aircraft.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: How the Luftwaffe destroyed Helensburgh's WW2 flying boats

In Professor Allen’s own words: “We dealt with unexpected phenomena!”

There was an element of danger, too, not just for the pilots and their air crew. A scientific colleague, H.G. White, was killed in an experimental seaplane crash.

Mr Allen, and other staff from his department, , including a young Frances Shedden, could have easily been in the Short Scion that fateful day.

MAEE came under the control of the Ministry of Aircraft, where completed reports were sent. These once top-secret documents are now held on file at the Imperial War Museum at Kew, London.

Professor Allen remembered colleagues like H.M. Garner, who as Sir Harry Garner later became Chief Scientist of Ministry of Aircraft Production.

Then there was Group Captain S.N. Webster, the commanding officer in 1943-44. He was a pilot with the high-speed flight of floatplanes which won the Schneider Trophy outright for Britain in 1931.

Some local residents found employment at MAEE, subject to signing the Official Secrets Act.

Among them were two Rhu ladies, secretary Mary MacCallum of Rhubaan, Upper Hall Road, and Frances Shedden from Brae House, who later married Jim McLaren, who worked on experimental installations.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: Memories of winter's icy grip at RAF Helensburgh

W.M. Inverarity, a mathematics teacher and astronomer from the Glasgow area also worked in the scientific office.

James Hamilton, a young graduate from Edinburgh University, joined Allen’s team and rose to the rank of senior scientific officer.

Hamilton was later knighted for his contribution to aviation, in particular for his work on the design of the Concorde supersonic aircraft.

Many friendships were made at RAF Helensburgh, but many colleagues went their separate ways after the war. Professor Allen remained a lifetime friend with Hamilton and Frances Shedden, who returned with him to MAEE Felixstowe.

Although a civilian, John Allen learned to fly in 1945 during his time with the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment — behind the controls of a test aircraft, an Auster Taylor’s floatplane which was unique to RAF Helensburgh.

Designed to operate in jungle conditions, where there were no airstrips, the ‘Auster with Boots’ was sent to Helensburgh in early January 1945 for testing and appraisal.

The Auster Taylor floatplane was a small, single-engined light mono plane based on a land version designed for reconnaissance duties in tight spots. Basically it was an existing Auster Taylor aircraft, fitted with less than ideal for purpose floats from a Queen Bee target aircraft.

READ MORE: Memorial honours the WW2 heroes of RAF Helensburgh

The serial number on the fuselage was TJ207, followed by a circled yellow P, standing for prototype.

Tests on the Gareloch were soon postponed following damage to the floats, and it was found that the weight of the Auster was too heavy for them and the skin around the front float attachment buckled.

TJ207 was taken away for modifications, and returned to the Gareloch on March 1, when it was found that now on the water, the floatplane proved very manoeuvrable.

MAEE test pilot Desmond ‘Dizzy’ Cooper reported that it was difficult to judge height above the water because of the curved side panels of the windscreen, unless the side window was wide open. In a crosswind, spray hit the propeller and the windscreen.

After further modifications, TJ207 returned on March 28 to resume testing. Test pilot Squadron Leader Desmond then reported easy and pleasant handling. Fifteen gallons of fuel was calculated to last two hours and 10 minutes, with a top speed of 156 mph.

MAEE civilian scientist John Allen sat in on the tests and learned to fly it using dual controls.

However, further testing at Helensburgh proved that the Auster float plane was not suitable for the tropical conditions it was expected to operate in. Also, properly designed floats should be used, as the Queen Bee floats were for a lighter biplane.

The decline of the Rising Sun in Burma and Malaya resulted in captured Japanese airfields becoming available to the Allies, and the need for a floatplane vanished overnight as land-based aircraft were used.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: Rhu was the WW2 home to RAF's 'Spitfires on floats'

Even so, testing continued after the end of the war with a second Auster floatplane, VF517, but peacetime was another nail in the coffin for the floatplane project.

Helicopters were becoming available to the military, and were able to drop into tight spots in the jungle for which the Auster floatplane was intended.

When MAEE left Helensburgh to return to Felixstowe, the need for military flying boats and floatplanes as a whole was declining. MAEE used a Cierva Hoverfly helicopter for trials.

There were a few new flying boats projects, like the Seaford flying boat. This was based on the Sunderland Mk 1V, which had been developed and tested at Helensburgh.

Another Helensburgh-inspired flying boat was the larger four-engined Shetland. The completed Shetland was delivered to Felixstowe in October 1945, but the prototype burned out in January 1946.

The days of the flying boat were almost over — despite achieving new heights thanks to RAF Helensburgh.

READ MORE: Click here to catch up with all the latest Helensburgh and Lomond news headlines

Email: milligeye@btinternet.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here