Our latest Eye on Millig column continues our fascinating look back at when and how clean water supplies came to Helensburgh and the surrounding area.

This week's instalment focuses on Rhu and Garelochhead...

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

THE villages of Helensburgh and district have had a variety of water sources in the past 200 years.

Originally they had a mixture of wells, springs and streams, and included some ingenious arrangements.

At Garelochhead, some villagers were able to take advantage of a large pond built to provide water for the steamers that once called at the pier, with a small charge.

The first of the local villages to initiate a modern water supply was Row, now Rhu, in 1870, while others like Rosneath and Clynder did not have such a facility until the late 1930s.

Any village wishing to set up a comprehensive public water supply faced significant challenges, because of the absence of the organisation and resources usually available to towns.

In 1867, however, a window of opportunity presented itself with the passage into law of the Public Health (Scotland) Act. This provided a mechanism for the introduction of utilities like water supply, drainage, and scavenging.

The process could be started by 10 ratepayers in a community signing a requisition and presenting it for consideration by the local authority.

Before 1889 that authority was the parochial board.

Parochial boards were established in 1845 to administer the Poor Law, but over time they accrued additional powers, and the 1867 Public Health Act made them the agency responsible for implementing measures like public water supply.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: The long journey to a clean water supply for Helensburgh

After 1889, the newly-formed county councils took over these functions. The boards continued to carry out their original role until 1895, when they were replaced by the more democratic parish councils.

So it was to Row Parochial Board that the village turned in 1870, armed with the necessary requisition.

Details are scant on the circumstances at Row, but certainly the Board would have had to consider the merits of the proposals, through what was known then as a Board of Supervision. If it was deemed feasible, the matter would next have been put before a public meeting.

If there was a promising response, a survey and costings would be commissioned. The plans would be tested by a plebiscite of ratepayers. If the necessary backing was forthcoming, work could then begin, with costs met by a charge on the rates.

Row successfully negotiated these various steps, and it became the Row Special Water Supply District.

In December 1870 the Dumbarton Herald newspaper reported that the waterworks scheme was already well in hand, with a reservoir under construction at the headwaters of Aldownick Glen — better known to romantics as Smugglers Glen.

The reservoir was small as the site was very restricted, being bounded on either side by steep ravines, and soon severe problems were being experienced.

In July 1884 the Helensburgh and Gareloch Times referred to residents having to run to neighbouring streams for fresh water, when it reported: “Intense heat has necessitated the supply being cut off for a few hours each day.

"If a week’s dry weather acts on the supply in this manner, what will a month’s dry weather do?”

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: How Helensburgh's water supply evolved and improved

At some stage, a second reservoir must have been added, because in 1891 the county medical officer of health said: “Row has a gravitational supply of water, impounded from springs and moorland, and stored in reservoirs.

"These lie at an altitude of 700 feet, and water is piped to all the houses.

“The population in the water district is above 862. The training ship ‘Empress’, by arrangement, is provided with the same supply.”

In 1889, with the responsibility for water supply having passed to Dumbarton County Council, it was not long before the new authority was receiving numerous complaints, initially about the excessive water pressure of up to 150lbs being encountered in lower parts of the village, with consequent damage to pipes and fittings.

It was agreed to install pressure reducing valves. However, the insufficient quantity of water also continued to surface, because by 1894, measures were being taken to build yet another reservoir.

It emerged that plans for such a move had been drawn up in 1887, but had subsequently been set aside. The consulting engineer for the earlier initiative was Mr McCall, of Forman and McCall, the engineers for the West Highland Railway, and he was asked again for his advice.

However, even for such a distinguished engineer, the nature of the site dictated compromise.

The end result was yet another small reservoir, so there was now a chain of three, strung out rather like a pearl necklace. Any alternative would have been excessively expensive.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: How a clean and safe public water supply reached Cove and Kilcreggan

That a new reservoir was most certainly overdue was highlighted by another water famine in 1895, the additional facility not being completed until the year after.

In operational terms, a water system like the one at Row was under the control of a superintendent, generally an experienced and self-employed local plumber.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Robert Shedden was superintendent, and was succeeded by his son, James, in 1904. He in turn was replaced by John Black.

The annual salary was £25, and there was an annual inspection by the Water Committee of the County Council.

Despite the best of attention, nothing could overcome the limitations of the site, and in 1913, during yet another drought, water had to be piped in from Helensburgh reservoirs to Row, via a two-and-a-half inch hosepipe.

The charge for this was six pence per 1,000 gallons. Water also had similarly to be supplied to Shandon Hydro and other places.

In 1933, the county medical officer of health reported that during the dry spell in 1931, a number of places, including parts of Garelochside, had suffered a lack of water.

His opinion was that only a comprehensive system of water supply for the whole western part of the County would address the chronic problem.

This was far from being the first time that pleas had been made for a joined-up system. It took many years before such aspirations were translated into reality.

During the Second World War, the lower of the Rhu reservoirs narrowly missed being hit by a bomb, and a large crater survives to bear witness to the incident.

It is tempting to think that the nearby Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment might have been the target, but a more likely scenario is that the crater resulted from a relatively small Luftwaffe night-time raid over the west of Scotland on October 24, 1940.

Twelve bombs and mines were dropped on the Luss and Arden area, 10 between Renton and Cardross, 14 between Rhu, Shandon and Glen Fruin, and 13 in and around the Rosneath peninsula. Two unexploded bombs were subsequently found at Garelochhead and Shandon.

The war, however, did result in some improvement of water supply, as a new reservoir was built by Royal Engineers at Auchengaich, just off Glen Fruin.

Work started in 1942, and the project was an acknowledgement of the enormous strain the military presence was placing on existing water supplies.

As well as supplying military needs, Auchengaich reservoir later eased the pressure on civilian requirements. The dam was more substantial than those normally found at local reservoirs — it had to be, as Auchengaich burn could run quite high at times.

There was found to be sufficient water for much of Garelochside, but it is not known if Rhu benefitted immediately.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: The last survivor of RAF Helensburgh durinng WW2 dies aged 99

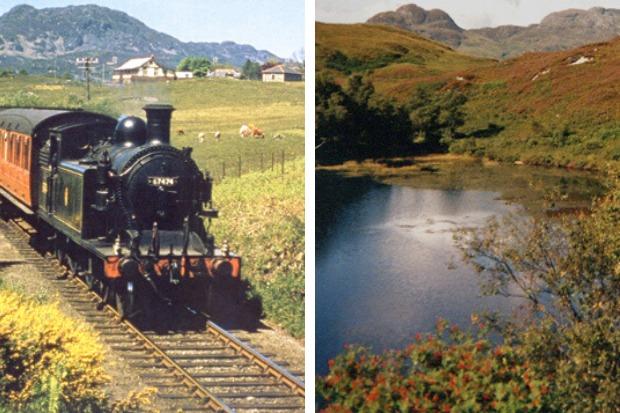

A spirit of joined-up water supplies was now afoot, and in the following decades further sources of water supply were utilised. Water from Loch Sloy came to Garelochside in 1967, while by 1979, a water main had connected Garelochhead with Garshake at Dumbarton.

Such developments led to the eventual redundancy of the Rhu reservoirs. However, they, along with the old filter house, survive as picturesque reminders of our heritage in water supply.

The next village to introduce a public water supply was Garelochhead, although it was a long process.

As far back as 1880, toes were tentatively being dipped in the water. In July of that year, the Lennox Herald newspaper reported that Garelochhead had submitted to the local authority plans for a combined water supply and drainage scheme.

That implies that the preliminary requisition had been submitted. Further, the newspaper noted that the Board of Supervision had indicated its support.

However, the proposals must have been for a fairly modest scheme, because estimated costs were £500-£600, which even by monetary values of the time, seems incredibly low.

Nothing more seems to have come of the scheme — perhaps it was a compromise that satisfied no-one.

Had the scheme been successful, it might have saved a great deal of ensuing anger and bitterness, because the ensuing decade saw major drainage problems.

Poor sewage disposal posed a major health concern for medical authorities and some residents. The introduction of a gravitationally fed water supply would have greatly facilitated implementation of a drainage system.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: The life story of Helensburgh engineer Professor Bob McMeeking

The catch was that such a combination would add to the overall cost, something that might well be fiercely opposed by some ratepayers.

This, too, was an era when the summer letting of seaside properties could represent a significant source of income for communities.

In 1890, the Helensburgh and Gareloch Times commented that failure to introduce a water supply and drainage scheme at Garelochhead was harming the popularity of the village.

Whether or not prompted by such criticism, a public meeting was held in September 1891 in the schoolroom at Garelochhead. In the chair was Francis C. Buchanan, of Clarinish, Row, a county councillor for many years.

He explained that the purpose was to consider the advisability of introducing a public water supply under the Public Health Act of 1867, and he referred to the way this had been achieved at Row some years earlier.

The meeting seems to have been fruitful, because later that month Councillor Buchanan was able to present to Dumbarton County Council a requisition for a public water supply, and a committee was appointed to investigate and report.

In December, another public meeting was convened, when Mr Buchanan advised that a survey had been carried out by Glasgow-based William Copland, an experienced chartered engineer.

The site chosen for a reservoir lay north east of Whistlefield, close to the MacAulay Burn.

It was envisaged that the supply would provide a water supply extending from the village as far as Dalandhui on the Rosneath Peninsula, and Rowmore, at the entrance to Faslane Bay. Whistlefield and Portincaple would also be supplied.

The land needed was 10 acres, with the feu duty payable to agents of the late Sir James Colquhoun being 10/- per acre. There was opposition from some quarters, but a majority agreed to press ahead.

The new water supply was opened in 1893, with Garelochhhead now a Special Water Supply District.

At the time of his survey, Mr Copland had been well aware of the potential offered by creating a dam across the MacAulay burn, which ran close to the reservoir, and which would probably have met all demands.

However, he had acknowledged that with a sizeable stream like this, the resulting costs would have been very much higher. There must be the suspicion that costs were kept to the minimum in order to keep ratepayers on board.

In a sense, the critics had a point. The county medical officer of health, in his annual report for 1897, pointed out that with Garelochhead having a water rate of 1/- 6d in the £, which was relatively high, this left only a balance of 11½d in the £ available for all other public health matters, including drainage schemes.

Had Clynder and Rosneath been part of the scheme, the shared costs would quite possibly have resulted in a better outcome.

email: milligeye@btinternet.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here