The final instalment in our Eye on Millig column's five-part series on the arrival of clean and safe public water supplies in Helensburgh and Lomond looks at Rosneath, Clynder, Cardross, Arrochar and Tarbet.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

THE villages of Rosneath and Clynder could have been in the Garelochhead Special Water Supply District set up in 1893.

It was claimed many years later that the two communities had been approached with a view to including them in this scheme, but they declined to take part.

The revelation came in 1934, when a proposed combined scheme for Garelochhead, Clynder and Rosneath was under consideration by the County Council.

The people of Garelochhead were reported to be against the idea, and it was a Garelochhead-based county councillor who made the allegation about the rebuff.

It is true that if the original scheme had been designed to accommodate the water needs of all three villages, it would have meant a substantially larger reservoir than what was actually built, though of course costs would have been more widely shared.

Known as Whistlefield Reservoir, the new facility was relatively small, had a very limited catchment area, and was not supplied by a stream of any substance.

The MacAulay burn, which ran close to the reservoir, could have been dammed, which would have met all demands.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: Part 1 of our series on Helensburgh and Lomond's public water supplies

However, the resulting costs would have been very much higher. There must be the suspicion that costs were kept to the minimum in order to keep ratepayers on board.

In a sense, the critics had a point. The county medical officer of health, in his annual report for 1897, pointed out that with Garelochhead having a water rate of 1/- 6d in the £, which was relatively high, this left only a balance of 11½d in the £ available for all other public health matters, including drainage schemes.

But had Clynder and Rosneath been part of the scheme, the shared costs would quite possibly have resulted in a better outcome.

Whistlefield Reservoir soon showed its limitations. In the summer of 1896, the Helensburgh and Gareloch Times stated: “Garelochhead reservoir has dried up. The people have had to fall back on old sources of water supply. This state of affairs has existed for ten days. The village of Row is also suffering from a water famine.”

In 1914 the newspaper reported on a meeting of the County Council, when it was stated that neither Garelochhead nor Row could be described as having a good water supply. Whistlefield reservoir was said to have a capacity of only two million gallons, which was quite inadequate for long periods of drought.

To rub salt in the wounds, the newspaper published a letter in 1926, written by someone calling himself “Moss Hag”, claiming that the water at Garelochhead was “so thick it could be burned as peat”.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: How Helensburgh's water supply developed and improved

At the 1934 meeting the cost of a reservoir serving Garelochhead, Clynder and Rosneath was quoted as £33,000. The matter would appear to have been taken forward, because a document of 1937 refers for the first time to Clynder Special Water Supply District, with a corresponding designation for Rosneath.

The Third Statistical Account of Scotland certainly mentions the laying of a water pipeline from Whistlefield to Clynder in 1937. But there is something of a puzzle here.

Comparison of maps show the surface area of Whistlefield reservoir had not changed over the years. Had the reservoir been deepened at some stage, there would have been evidence of alterations to the embankment, but scrutiny of the site affords scant evidence — the embankment is quite low, and there are no obvious signs of an intake from the adjacent MacAulay burn.

A pipeline to Clynder and Rosneath might have been laid, but given the history of Garelochhead reservoir, it is hard to see how an unchanged system could have coped with a big increase in demand.

Evidence suggests that when the American Navy came to Rosneath in 1942, there was no public water supply.

One resident noted the Americans' disdain for the local water supply arrangements, and he added: “The local people had always depended on hillside streams and wells for their water.”

Another remarked: “We had never thought there was anything wrong with our water. It was peat-stained during wet weather, but we never thought of it as a health hazard. We liked it.”

The Americans went their own way, refurbishing the old dam at Millbrae, and installing a custom-built water treatment plant. The corrugated iron building housing the facility is still beside the main road.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: How a clean water supply reached Cove and Kilcreggan

As far back as 1912, Clynder harboured ambitions of becoming a Special Water Supply District. Plans were drawn up for a reservoir, but nothing further happened.

Maps show a reservoir at the head of Clachan Glen, Rosneath, and another small dam on the Hatton Burn, above Barremman, but whatever their function, they did not form part of a public water supply.

Wartime construction of Auchengaich reservoir, near the head of Glen Fruin, came to the rescue, offering a greatly improved water supply for much of Garelochside and the Rosneath Peninsula.

In 1967, the provision of further water supplies from Loch Sloy signalled the end of the local water shortage.

Today, Whistlefield reservoir survives, close to the wartime Yankee Road. A sign beside the reservoir proclaims ‘West of Scotland Water’. As this body was in operation between 1995 and 2002, it offers a clue as to the last phase of the facility as a working reservoir.

Also obsolete are an array of rusting War Department signs ringing the reservoir, instructing military personnel to stay outside the old iron perimeter fence.

The water storage tank beside the Whistlefield roundabout advertises not only West of Scotland Water, but also its predecessor, Strathclyde Water (1975-1995).

The nearby Filter House, a trim little building of stone and a slate roof, was demolished in 2004, and replaced by a modern house.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: When Rhu and Garelochhead were added to public water supply network

At Cardross, the familiar story emerges of inadequate water supplies, set against the background of a growing population.

The old public reservoir was near Asker Farm, high on the moors above the village. It was quite small, with a capacity of under a million gallons. It may have served well, but as the village grew, so did demand.

In his annual report for 1933, the county medical officer of health, Dr Thomas Lauder Thomson, refers to the drought of 1931: “Cardross, certain parts of the Gareloch, Arrochar, and Kilmaronock, all suffered, more or less. Negotiations for additional supply at Cardross assumed quite a helpful aspect at the end of the year.”

He acknowledged that water samples taken from Asker were classified as “good”, and his reference to an extra supply for Cardross may refer to Carman reservoir, above Renton.

That reservoir was originally constructed as a private water supply by the Turnbull family, who owned several factories in the Vale of Leven. It was in place by 1860.

Thanks mainly to the booming textiles industry, the rapid growth of the village of Renton in the 19th century led to the pressing need for a better water supply.

So in 1886, Carman reservoir was adopted by Cardross Parochial Board for that purpose. It was enlarged and put to use under the name of Renton Special Water Supply District.

In 1906 the construction of a new reservoir at Glen Finlas brought an excellent water supply to the Vale of Leven. Over the years, water from this reservoir also supplied places as far apart as Croftamie, Dumbarton, and Loch Lomondside, at least as far north as Luss. It continues to contribute to the water supply chain today.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: Loch Long mansion's link to Glasgow river pollution fears

Renton, too, eventually became a beneficiary of this new supply, although thanks to Carman reservoir, it already had an abundant supply of good water. The capacity was more than 78,500,000 gallons, which is more than was contained in the two largest Helensburgh reservoirs combined.

The village of Cardross was enabled to take a supply of water from Carman reservoir in the post-war period.

The entry for Cardross village in the Third Statistical Account for Scotland (1950; revised 1956) states: “Only a few years ago, during a dry summer, water had to be supplied to the houses from barrels set up at convenient points”. But the writer said that thanks to the supply from Carman, that problem no longer existed.

Even so, Asker reservoir was by no means rendered redundant, and into the 1960s it was still supplying water to the community. Today, neither Asker nor Carman functions as part of the water supply.

Carman reservoir does continue to be used, but only as a trout fishery.

Dr Thomson’s 1933 report also made reference to an analysis of water taken from Shear’s Well at Cardross, which he stated was once part of the public supply. This was one of five wells tested, and all were found to contain nitrates.

Shear’s Well came in for particular criticism, as it was found to be heavily contaminated, containing the equivalent of one part average sewage to 54 parts water.

Also known as St Shear’s Well and St Serf’s Well, this is an interesting historical entity in its own right. It lies close to the Auld Kirk of Cardross, located in what is now Levengrove Park, Dumbarton.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: Eight members of Cardross family died in Clyde boating tragedy in 1849

St Serf is one of those Dark Age evangelists whose story remains fairly obscure. He is said to have been particularly associated with Culross in Fife, but the good saint seems to have travelled west at some stage. Loch Lomond has a St Serf’s Inch.

St Serf’s Well once formed part of the public water supply. It was the main source of water for the ancient burgh and county town of Dumbarton for well over a century.

A Town Council minute of 1713 states: “In consideration of the want of good water in the town, the council resolve to convey St Shear’s Well across the Leven, Sir James Smollett to speak to the Laird of Kirkton thereanent, and to look for some skilled person to execute the work.”

A minute the following year records that a Mr Cairnaby, Glasgow, was to bring St Shear’s Well water into the town for £54. The water was conveyed through a pipe laid on the bed of the River Leven, the second fastest flowing river in Scotland.

Incredibly, this arrangement lasted until 1860, when a modern supply was obtained from reservoirs in the Kilpatrick Hills.

Dumbarton was repeatedly obliged to look for additional supplies of water over the years. In 1906, its ambition was to take water from Loch Sloy, but in this it was thwarted by Dumbarton County Council, which had its own eyes on the loch.

By the early 1960s Dumbarton was receiving some of its water from Finlas Reservoir, and some from Carman Reservoir, along with water from its own reservoirs in the Kilpatrick Hills.

With the construction of a barrage across the River Leven at Balloch in 1971, and utilisation of Loch Lomond as a source of water, the potential it offered helped solve the water needs of places like Dumbarton.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: Clyde paddle steamer was a jet-powered pioneer

A public water supply for Arrochar was instituted around 1937. A reservoir was built on the burn above Tyness, and it performed well. In 1949, the same supply was extended to include Tarbet.

The county medical officer of health said in 1962 the supply was “satisfactory”.

In 1967, with the laying of a water main from Loch Sloy to Garelochside, Arrochar and Tarbet were also connected to the facility. This was apt, as some of the houses at Ballyhennan, Tarbet, were built for Hydro Board staff employed at Loch Sloy.

As far back as 1906, both Dumbarton Burgh and County Councils had their eyes on Loch Sloy as a potential source of water. However the loch was also being sized up as the possible site of a hydro scheme.

The plan was to conduct water by canal down to Inveruglas, where the power plant would be sited. Another hydro scheme was proposed just before the First World War, and plans emerged yet again in the 1920s and 1930s. But nothing transpired.

It was realised early that, despite the very high annual rainfall at the loch, the amount of water available for a hydro-electric scheme would be insufficient. To make the plans viable, streams beyond the catchment area would need to be tapped.

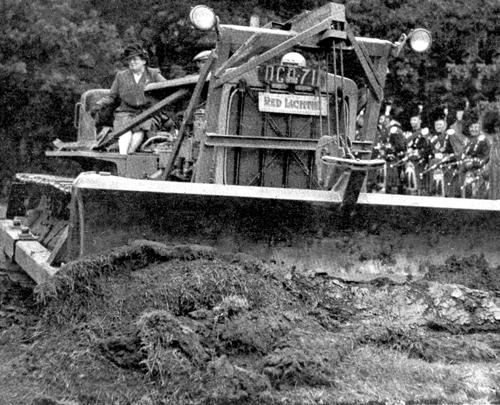

When the first sod of the hydro scheme was cut in May 1945, it was on the basis that this additional source of water would be integral to the success of the project. Reaching out beyond the natural catchment area

may have been influenced by the recognition that there was competing demand from the water supply industry.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: The Helensburgh men who survived WW2 'Railway of Death'

Dumbarton County Council opposed the hydro scheme on the grounds that it needed the water for human consumption. At some stage, agreement seems to have been reached that up to three million gallons a day could be taken, should the need arise.

That dimension came to a head in the early 1960s because of the anticipated arrival of the Polaris defence system at Faslane, and the projected increase in population, both military and civilian.

With the collaboration of the County Council and the Admiralty, a filter house was built in the glen below the dam, and a 12-inch water main to Garelochside laid and brought into use in 1967.

Loch Sloy continues to serve today as an integral part of the water supply network.

An historical footnote is that Loch Sloy featured in what is thought to have been the very last Luftwaffe raid on the West of Scotland, on April 25, 1943.

A good deal of the preparatory work for the hydro scheme was carried out by Garelochside-based German prisoners of war, and after months of enemy inactivity, the attack came as a complete surprise.

It began with the dropping of bombs in the Annan district of Dumfriesshire. Bizarrely, the next bombs were dropped 20 minutes later at the north end of Loch Sloy.

The attack progressed to Glasgow, but there were few human casualties.

Email: milligeye@btinternet.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here