In this week's Eye on Millig column, Leslie Maxwell resumes his look back at life in the hamlet of Glenmallan on the east shore of Loch Long – now no more, save for a Ministry of Defence refuelling jetty and plans for visits from some of the Royal Navy's largest ships.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

WHEN compulsory education for primary age children began in 1872, it posed a challenge for hamlets some distance from towns and villages, such as Glenmallan on Loch Longside.

The educational body set up to administer the system, the School Board of the Parish of Row, did however come up with a plan to build a school there as early as 1873.

It was noted that Mr Caird and Mr White, proprietors of the mansion houses of Finnart and Arddarroch respectively, had between them 12 children of school age, 5-13, among their staff.

There were also five children living at Strone at Glenmallan, as well as nine at Craggan, at the Glen Douglas road end, and 11 at Portincaple.

Sadly, though, the ratepayers did not deem the expense of a school justifiable.

The main option for children at Glenmallan was to make their way to Garelochhead School — and a logbook entry for that school records that twins aged five, with their older siblings, faced a five-mile walk to school. Any children living further away would surely have found this journey beyond them.

By 1905, several children of the McGlone family living at a cottage called Thorniebank, about two miles north of Glenmallan, were attending Glen Douglas School.

That entailed a walk of more than three miles and a climb of 500 feet – a tough call for a young child, especially in bad weather.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: The Loch Long hamlet of Glenmallan is no more

By 1924, the next generation of McGlone children were facing the same daily journey, initially from Thorniebank, but a family move to Glenmallan in 1926 saw them face a daily commute of five miles there and back.

Not surprisingly, school records show that there were frequent absences. But that situation was about to change.

In the summer of 1926, a school came into being at Glenmallan. It did not operate from custom-built premises, but from one of the cottages.

Elizabeth Wiltshire, a qualified teacher, was appointed, with accommodation provided for her at five shillings a week.

Almost certainly, she was a daughter of Albert Wiltshire, the stationmaster at Garelochhead. Another daughter, Grace, was a well-known teacher.

Glenmallan School was classified as a ‘side school’. That meant it came under a larger school, Garelochhead.

The headmaster, Thomas Neilson, cycled to Glenmallan on the opening day, but as it happened, attendance was low, owing to illness and bad weather.

For a number of years, he visited once a week to check on progress, and an HMI report in 1927 praised the good work being done at the new school.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: Loch Long mansion's link to Glasgow river pollution fears

However, the arrangements for teacher accommodation did not work well, and the subject came up at a meeting of the Helensburgh District School Management Committee in 1928.

The chairman approached the Education Authority about the problem, but he was informed there was no lack of teachers, and accommodation could be had at Whistlefield and Garelochhead.

The school was seen as purely temporary. It was also pointed out that a local lady was running it, and if they had to recruit from further afield, there would be no difficulty in getting a teacher.

The chairman suggested that when a new school was built, it should be recommended that teacher accommodation be provided. This was agreed.

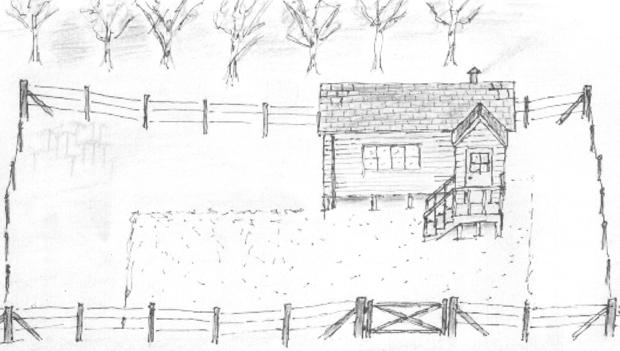

A custom-built school for Glenmallan opened its doors in 1929. It was a small, single room wooden building, built on sloping ground,with the frontage was on a stilt-like framework. There were ten pupils.

That same year, Miss Wiltshire left for a teaching post at Rhu, and Miss Agnes Blake was appointed in her place.

This coincided with a major change in administration. Education had been a function of education authorities since 1918, but responsibility was now vested in city and county councils.

Glenmallan and other local schools now came under Dumbarton County Council Education, an arrangement that lasted through the rest of the life of the school and beyond.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: The hidden history of empty Loch Long mansion house

When HM Inspectors visited the school in 1931, there were 13 pupils, and their report was again favourable.

“Save for a recent fall due to influenza, attendance has maintained a good level during the current session," they said.

“The premises, which are of a temporary nature, provide adequate accommodation with good light.

“Heating is effected by a stove of a type which does not conform to the Building Regulations — a thermometer should be supplied to enable the teacher to regulate the temperature, which on the day of the inspection was too high.

“The pupils are instructed by a young probationer who gives much promise and is already achieving creditable results.

"In the basic subjects, good progress is secured by methodical teaching on modern lines, and special mention may be made of the standards aimed at and attained in music and repetition of poetry.”

This was the era of the Great Depression, and all communities struggled through difficult economic conditions.

Former Finnart resident and pupil Winnie Bolton recalled how tough it was, but said that at the same time people could be resourceful.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: Glasgow children came to Helensburgh and beyond for 'Fresh Air Fortnight'

“It was a hard life,” she said. “We were all poor, but we didn’t know the difference as we were all in the same boat.

“The local landlords forbade the taking of rabbits and other game from their lands. But Johnny McGlone always managed to poach something for his pot, and often shared with us — he would stop by our cottage and check if anything was needed.

“Between that, and the various kinds of fish to be taken from the loch, the mussels and clabbydoos to be gathered from the shore, and our home-grown vegetables, we nearly always fared well for food.

“What we did lack was milk and dairy products, and for that I am suffering today from osteoporosis.”

John McGlone, the local roadman, who lived with his family at Strone Old Tollhouse, helped at the school. There was a stove fuelled by coal, and he filled scuttles, and probably emptied the ashes and re-set the fire.

There was also the delicate matter of emptying the dry closet, which was discreetly located behind the coal shed, and burying the contents. More than likely, that was another task that would have fallen to him, paid or unpaid.

In 1933, Annie Turner, later Mrs Walker, was appointed teacher.

An honours graduate of Glasgow University, she commented in later life of the difficulties in obtaining a suitable teaching post, such was the prejudice that then existed against female teachers, even well qualified ones.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: Did the oldest Scotsman really live on the shore of Loch Long?

The only teaching post available to her was at Glenmallan.

A chronic problem, and one that was to persist through the lifespan of the school, was the lack of teacher accommodation. The post was, however a foot in the door, and Annie was able to move from Glenmallan to Glen Fruin, and eventually gain a post in secondary education.

Annie’s early career was typical — Glenmallan saw a succession of young unmarried female teachers at the school for a limited period, before they moved on or left to get married.

At that time, any female teacher who married had to quit teaching, although that would later change.

Glen Douglas School also suffered initially from a lack of suitable teacher accommodation. A turnover of young unmarried female teachers was again the order of the day.

This school was conducted from different farms, until a custom-built school was provided in 1890.

The lack of teacher accommodation continued until 1900, when an annexe was added. Immediately after, a married male teacher was appointed.

Glenmallan School never had such dedicated teacher accommodation provided, and so staff continued to make their way to Glenmallan as best they could, usually from Helensburgh — a major challenge in its own right.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: The Cardross minister's son who fought to abolish slavery

What is remarkable is that the school always performed to a high level, while it is clear from testimonials of former pupils that there was enormous respect and affection for the teachers, and for the school in general.

With harsh economic conditions continuing to bite, the roll had shrunk to three pupils by the time Annie Turner took up her post.

Retrenchment was also taking place at Garelochhead, where the staffing complement was reduced.

In 1932, Thomas Neilson was informed that because of the cutbacks, he would have to reduce his visits to Glenmallan from a weekly to a monthly basis. This was brought about, despite his protests.

He faithfully continued his supervision, still travelling by bicycle. As well as his visits, the County Director of Education made an annual trip, while medical and dental visits also took place.

In 1938, Thomas Neilson was told that Glenmallan would no longer form part of his responsibility, but would thereafter function as a separate school, probably as part of a wider rationalisation of educational provision.

Soon after, the dark clouds of World War Two descended. For the school, however, life continued, and thanks to the national scheme of evacuating children from urban areas to the countryside, Glenmallan saw an increased roll.

There may be a perception that evacuees had little or no say in their destinations, but this would seem to have been far from the case, at least in some instances. The key seems to have been the presence of family in the countryside.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: How experts at RAF Helensburgh tried to fix WW2 'flying coffin'

It is known that a number of evacuees who lacked such contacts, and who were sent to places like Arrochar and Glen Douglas, often left for home after a relatively short period.

A big factor in the Glenmallan area during the war years was the building of oil jetties, storage tanks and a pipeline along the road at Finnart, while the Admiralty Range at Arrochar was much used to test torpedoes and depth charges.

The school had an Anderson shelter provided, with practice drills as rehearsal for an aerial attack.

The post war era saw major changes in society, and this was reflected at Glenmallan School. It closed its doors around 1947-48, as educational provision was overhauled.

Glen Fruin and several other small schools also came to an end at this time, and children were taken by bus to bigger schools.

Glenmallan pupils were transported to Arrochar School. In due course, a bus was also laid on to take secondary pupils to Helensburgh.

The school building was demolished, and in the grounds was built a new roadman’s cottage in 1953-54. The McGlone family moved in from their former home at the Old Tollhouse.

Email: milligeye@btinternet.com

READ MORE: Check out all the latest news headlines from around Helensburgh and Lomond here

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here