THE latest Eye on Millig column, by Leslie Maxwell and Robin Bird, looks back on the Catalina flying boats which were based at RAF Helensburgh during the Second World War.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

THE ‘Lend Lease’ Consolidated Catalina flying boats on the way to World War Two’s RAF Helensburgh for testing and modifications had to make a hazardous non-stop flight across the Atlantic.

Ferry pilots landed first at Greenock, the reception destination, descending through cloud into fields of mushroom-like barrage balloons.

When Catalinas started to arrive, Greenock then suffered two harrowing nights of Luftwaffe bombing on May 6 and 7, 1941. So anti-aircraft defences around Greenock and Helensburgh were looking out for ‘enemy’ aircraft.

Catalinas were not yet a familiar sight and so risked friendly fire, and those going on to RAF Helensburgh faced added navigational risks.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: Wartime secrets from RAF Helensburgh emerge

The ferry pilots and crew were unfamiliar with the west coast of Scotland, and the mountains and hills around Greenock, Helensburgh and Garelochside could catch out low flying or circling pilots.

The 3,400-mile non-stop flight to Greenock claimed some Lend Lease aircraft before arrival - they just went missing.

Luftwaffe Condors, on the prowl for these Cats, were an added threat. U-Boat fire was yet another hazard for aircraft flying low because of bad weather conditions.

Catalinas started arriving at Helensburgh in 1941, and vital pilot notes outlining the approach to Greenock and Helensburgh have come to light. These were in addition to the Consolidated Catalina pilots manual.

It was quite a different flight experience for the American crew of Britain’s first Catalina, P9630.

It was delivered during July 1939 to the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment at Felixstowe, before the establishment was moved north to Garelochside.

This first historic non-stop Atlantic flight made aviation history. The press waited to record the splash down - and the crew emerged wearing summer clothes and carrying golf clubs.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: The mission from Helensburgh that shaped the outcome of WW2

When MAEE evacuated to Rhu at the outbreak of war a pilot to fly Catalina P9630 could not be found, so a Canadian pilot had to fly to Felixstowe.

The initial test result on P9630 at Helensburgh was enough for Prime Minister Winston Churchill to order more Catalinas from the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation in America.

It was just as well that the MAEE appraisal was positive, as on February 10 1940, P9630 crashed while flying from Rhu to Dumbarton.

Churchill’s first order for seven Catalinas started with serial number AM264, which went straight to Helensburgh in January 1941. But AM 265 was lost somewhere over the Atlantic.

Initially, only Greenock received Catalinas, and later Largs, which did not have a balloon problem.

Most Catalinas were converted to RAF specification at Scottish Aviation at Greenock, where there were hangars, slipways and an electric winch capable of hauling up flying boats.

Catalina crews could activate darkened lighthouses, which had been blacked out to prevent the enemy using them for navigation, in order to determine their true position. Admiralty codes were used to turn lights on.

Industrial haze, close proximity of high ground and tethered barrage balloons on both land and ships were potential hazards approaching Greenock.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: RAF Helensburgh pilots led the battle to beat German U-Boats

Minimum limits for the approach demanded visibility of two miles with a 1,000 ft cloud ceiling. If conditions fell below that, the pilot had to abort Greenock and instead divert to Stranraer.

The ferry pilots notes stressed that under no circumstances should landings be attempted at Greenock during hours of darkness.

They added: “If the estimated time of arrival slips to dusk, or later, divert to Castle Archdale in Northern Ireland.”

There was a warning covering descending to the height of barrage balloons. At Greenock, green welcome flares were fired from a reception launch - but if a red flare was fired aircraft must overshoot and repeat an approach.

There was a final warning about high ground before flying boats splashed down to stop short at red chequered buoys. On arrival the Catalinas were towed to moorings buoys.

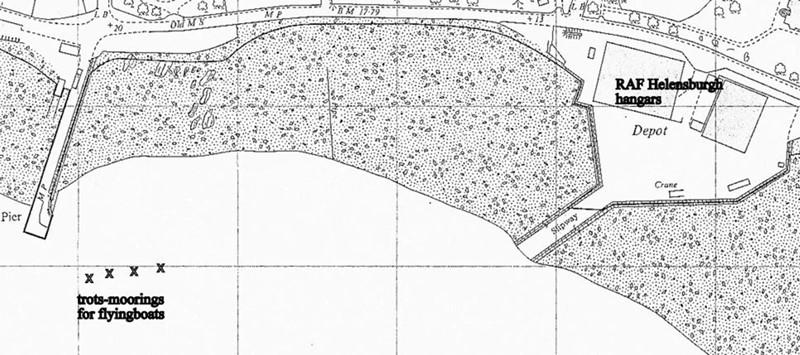

Although Greenock is opposite Helensburgh, the subsequent four-mile flight was not risk free, and RAF Helensburgh was informed of the departure and estimated time of arrival.

Ferry pilots were reminded that Helensburgh was a seaplane base with the likelihood of moving aircraft, plus moored flying boats.

There were further warnings about hills for descending or circling pilots. The hazards were clearly marked on the map in the notes.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: The colourful history of former Loch Long estate, Gortan

A Saro Lerwick belonging to RAF Helensburgh had already crashed at a hilly location above Faslane killing all aboard - and its pilot had known the area.

Catalinas landing on the Gareloch reduced speed with floats down, and the pilots notes recommended touch-down on a normal landing in a take-off attitude.

As the aircraft lost speed the control column was eased back and held hard back. The engines were shut off. The propellers were trimmed with one blade on each engine pointing downwards towards the hull.

The aircraft tender craft was from Rhu. It helped secure aircraft to the mooring and pick up the crew, who would then be debriefed and officers found accommodation at the Royal Northern Yacht Club.

After a suitable rest they returned across the Atlantic to pick up another aircraft to ferry.

Occasionally a pilot would remain at Helensburgh for a while for instruction to show how to handle the later Lend Lease Consolidated Coronado and Martin Mariners, which were totally new types of aircraft for RAF crews.

Captain Gentry, for example, stayed at Helensburgh with Corando JX470, and his exploits over the Atlantic also made aviation history.

READ MORE: Eye on Millig: First Helensburgh newspaper can now be read online

The first full report on a delivery flight Catalina concerned AH550. It came from Bermuda via Greenock, a distance of approximately 3,000 nautical miles.

On take-off the Catalina had 1,457 gallons for the long flight taking more than 27 hours. The fuel tanks when checked at Helensburgh only contained some 100 gallons.

Even a short flight from Helensburgh had potential risks, which was illustrated by Catalina AH533.

It had just been serviced at Helensburgh and the crew refreshed overnight, but mist and cloud caused the pilot to misjudge high ground on the Isle of Jura.

It crashed, burst into flames, killing everyone except one survivor. This was also a reminder of the danger of hills and mountains.

There was a rumour that a captured German Dornier was at Greenock during 1940 and it became a post war urban myth. However there were no captured Dornier flying boats in Britain at the time.

A Helensburgh Heritage Trust copyright photo from the Bird Collection shows that the flying boat at Scottish Aviation at Greenock was actually one of the four Heinkel 115 floatplanes which were flown to Helensburgh by escaping Norwegian pilots.

It was there to be prepared for clandestine operations.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

* Email your suggestions for historical Helensburgh and Lomond topics that could be covered in future Eye on Millig articles to milligeye@btinternet.com.

Click here for all the latest Helensburgh and Lomond headlines

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel