THE CENTENARY of the K.13 submarine disaster in the Gareloch will be marked at Faslane Cemetery — where the 32 victims are buried — with a memorial service on Sunday.

The steam-propelled submarine sank in the loch during sea trials after sea water entered the engine room. There were 80 men on board, mostly navymen but with some civilians.

I told the tragic story two weeks ago, but now a fascinating new account has been found by Rhu man Alan Dundas.

He tells me: “I found it in the Lithgow Group Winter 1952 magazine that my late mother-in-law had in her papers. My wife’s grandfather, Peter Baxter, was a director in a number of Lithgow companies at that period.”

It is a long and fascinating article by Alastair Borthwick illustrated with sketches, which will need to be completed next week. Here is the first part . . .

On the afternoon of 29th January 1917 a housemaid at Shandon Hydro told friends that she had seen two men swimming in the Gareloch out from the shore.

They had, she said, shouted “Oh” and then flung up their arms and disappeared.

About the same time doubts were crossing the minds of two other people on the Gareloch.

One of them was the captain of the submarine E.50 who had been watching the K.13, a new submarine undergoing her acceptance trials, diving offshore from Shandon.

He could not put his finger on the trouble, but there had been something about that last dive which had not looked quite right. He had not liked the look of it.

The other man was Mr Cleghorn, a director of Fairfield, who had watched the dive from a tender. His firm had built the submarine, and fourteen of his men were on board.

The thing which made him a very worried man indeed was the amount of air which had come to the surface after the submarine had disappeared.

The housemaid’s friends refused to listen when she told her story — three days were to pass before anyone took it seriously; but the others wasted no time.

The captain sailed over and dropped a buoy to mark the spot; and Mr Cleghorn telephoned Fairfield immediately to set in train the long series of operations which were to make the K.13 rescue one of the classics of submarine salvage.

At this stage the K.13 was lying on the floor of the Gareloch, 55 feet down, with her bows in the mud, her interior half-full of water, and thirty of the eighty people in her drowned.

She had reached this position in a very simple way.

A member of her naval crew — the vessel had been accepted, and the Fairfield men were only standing by — had signalled before the dive that all openings to the engine-room had been closed down.

But they had not all been closed. Four air inlets to the boiler-room were wide open.

Almost as soon as the dive began the captain knew there was something far wrong; air pressure was drumming in his ears and the depth gauges showed that she was going down much too quickly.

Orders to blow all tanks produced no result. Water began to spout from one of the control-room speaking tubes. The K.13 continued to sink. A few seconds later she came gently to rest on the bottom.

The situation facing the fifty men still alive was a desperate one, for in those days salvage was not the highly organised affair it now is, and no escape apparatus or even an efficient escape-hatch existed in the submarine.

They calculated they had enough air for eight hours, plus an unknown quantity from the compressed air supply; and, so far as they knew, no rescue attempt could even be started until next day.

They had not been due to surface until dusk, and — knowing nothing of the alarm already being felt by their friends — they assumed they would not be missed until then, by which time it would be too dark for anything to be done that night.

The only items on the credit side appeared to be that the after bulkheads were holding under the strain, and the batteries were fully charged; they had light, and the pumps and the air compressor could be worked.

They settled down to wait. Few of them really believed they would ever see blue sky again, for already, after only a few hours, air was running short.

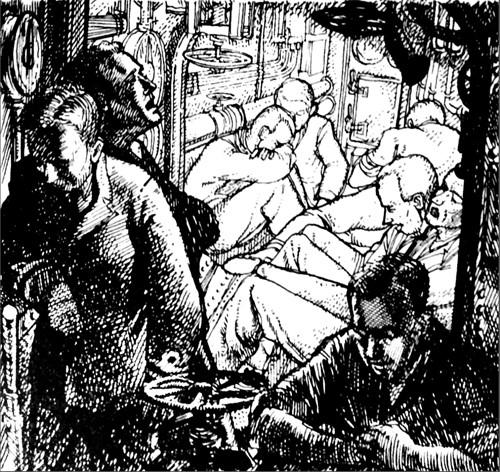

“As the air in our submerged prison became more and more foul,” wrote Mr Percy Hillhouse, naval architect on the Fairfield staff, “so did our breathing be-come more and more difficult, and we had to inhale and exhale with painful rapidity.

“For some the process was carried on only under great pain and difficulty. Many found standing the easiest posture.

“The great majority, however, were rendered more or less inert and apathetic, and lay down anywhere and everywhere, half asleep, half awake, and breathing or snoring noisily. And so the long night passed away.”

Meanwhile a great deal had been happening on the surface. Far from waiting until dawn, the rescuers had been at work almost from the moment when the submarine submerged.

The E.50 and the gunboat ‘Gossamer’ had been standing by continuously, and by 2 a.m. on the 30th, eleven hours after the accident, the ‘Gossamer’ located the K.13 by grappling.

The gunboat had a diving suit, but no diver. A car was sent to Fairfield for the firm’s diver, but when he started to go down to the submarine the ‘Gossamer’ suit, an old one, burst, and the diver was nearly drowned.

Another car trip was needed to fetch the Fairfield suit; and so it was that at eight o’clock in the morning the imprisoned men at last heard footsteps and tapping on the outside of the hull.

They could not even raise a cheer. Indeed, most of them were almost indifferent.

Although they had been below only 17 hours, the air was already so bad that a match could not burn in it. Yet, as events turned out, they were to survive on that same air for 25 hours more.

The K.13 carried two commanders, one of them her own and the other the captain of a sister vessel at that time being built at Fairfield, and these two gentlemen well knew that the chances of rescue would be doubled if the rescuers knew exactly what they were tackling.

When contact was made, they tried to tap out in Morse full details of the situation in the submarine; but for some reason these efforts failed.

They decided that one of them would have to try to reach the surface. Lieutenant Commander Godfrey Herbert of the K.13 was willing to try, but his duty was to remain with his ship until the last.

Commander Francis H.H.Goodhart DSO declared that it would be better for him to make the attempt himself, and so it was decided.

The plan of escape sounds clumsy and complicated in an age when escape hatches are standard equipment in submarines.

Not only did the conning tower have hatches, one in the floor and one in the roof, which could only be opened and closed from below, but there were no arrangements for draining the conning tower.

Furthermore, anyone escaping from it would not find himself clear of the submarine, but swimming in a wheelhouse which was built round the tower, searching for a small hatch in a far corner of the roof.

From this it will be seen that for one man to escape and still leave the way clear for others to follow later if necessary, a second man would have to go with him into the conning tower to close.

Lt Cdr Herbert decided to be the second man; and in preparation for the attempt he ordered the projector compass and its tube to be removed from the hatch, the idea being to give more space and to leave a hole — with a valve to open and close it — in the floor through which the tower could be drained.

He also ordered the steam whistle pipe to be connected up to the compressed air system.

The plan was for both men to enter the tower and close the hatch behind them. Those in the submarine would secure it from below.

Once inside they would open the sea valve and gradually flood the tower until the pressure was high enough for the upper hatch to be opened.

Once that was done, high pressure air was to be turned on, and Cdr Goodhart was to be carried by it upwards and outwards in the direction, it was hoped, of the little hatch in the wheelhouse roof.

As soon as he was gone, Commander Herbert would shut off the air supply, close and clip the outer hatch, and knock loudly on the floor. Those below would then open the drain valve to reduce the pressure and allow the Commander to lift the hatch in the floor and so return.

This was the best that could be done, but it was a complicated plan to be worked at high speed, underwater, in an enclosed space. It did not work as intended.

n To be continued next week.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article